An intense X5.1-class solar flare on 11 November 2025 and a sequence of fast coronal mass ejections (CMEs) have driven a G4 (severe) geomagnetic storm at Earth, raising the risk of disruptions to satellites, power infrastructure and GNSS-based navigation. A third CME, observed with an initial speed near 1500 km/s, is forecast to arrive between late 12 November and early 13 November UTC, with both timing and severity subject to uncertainty. Current assessments indicate no direct biological risk to people on Earth.

Source: European Space Agency update (last updated 12 November 2025, 14:00 CET).

Event timeline and observations

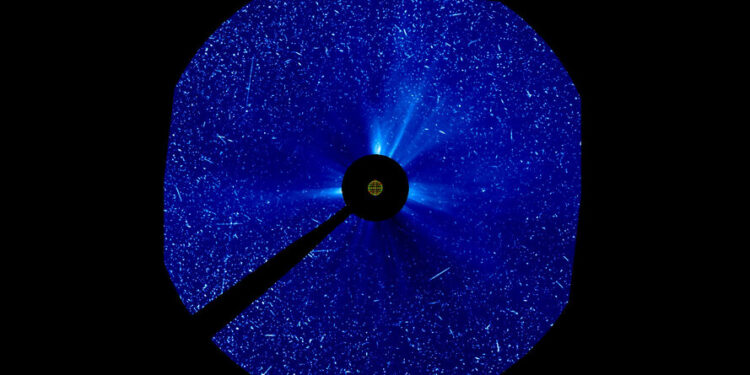

Earlier this week, two strong X-class flares from NOAA Active Region 14274 produced CMEs that reached Earth and triggered a severe geomagnetic storm. On 11 November, the Sun produced a more powerful X5.1 flare peaking around 10:04 UTC. Shock fronts were seen propagating from the active region in extreme ultraviolet imagery from SDO/AIA. Less than an hour later, a CME was detected by SOHO/LASCO and GOES-19/CCOR-1 coronagraphs with an initial speed of roughly 1500 km/s.

ESA expects elevated space weather conditions to persist through the second half of the week as multiple eruptions continue from the same active region. Forecasts may change as additional observations arrive.

Expected impacts and affected regions

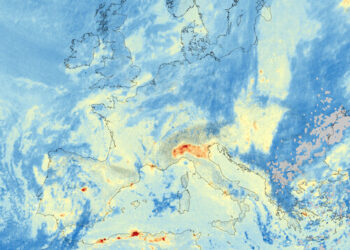

Major flares and CMEs can degrade radio communication and satellite navigation on the Sun-facing side of Earth. For the 11 November event, daylit regions at the time of the flare included Europe, Africa and Asia. The ongoing storm and potential third CME increase the likelihood of further disturbances.

- Satellite operations: higher risk of single-event upsets and surface charging; increased atmospheric drag in low Earth orbit, complicating tracking and conjunction assessment.

- Navigation and communications: GNSS position and timing degradation or outages; shortwave/HF radio blackouts and transionospheric signal errors, especially on the dayside.

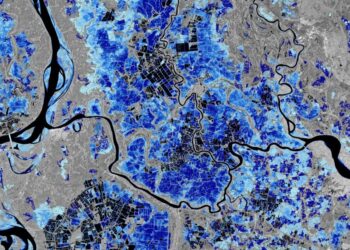

- Power systems: geomagnetically induced currents may stress transformers and long conductive infrastructure such as transmission lines and pipelines.

- Auroras: enhanced auroral activity is likely, with possible visibility at lower-than-usual latitudes.

Monitoring and forecasting upgrades

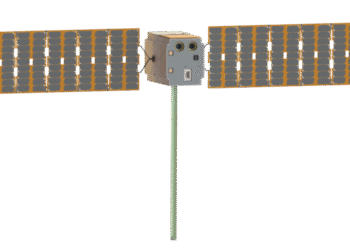

ESA is coordinating inputs from its expert service centres to refine arrival-time and impact estimates. Reducing uncertainty in CME arrival and storm severity is a key objective for upcoming missions. The Vigil mission, planned for launch in 2031 to the Sun–Earth L5 point, will provide side-on views of emerging solar activity for earlier and more continuous warnings. Today’s near-Earth monitors at L1 typically provide tens of minutes of lead time; a proposed deep-space “Shield” mission concept at roughly 15 million km could extend this to about two and a half hours.

How solar storms unfold

- Electromagnetic pulse: Light-speed radiation from a flare reaches Earth in about eight minutes, potentially disrupting shortwave radio and causing GNSS errors.

- Solar energetic particles: High-energy protons and other particles can arrive minutes to hours after the flare, posing hazards to spacecraft and high-altitude operations.

- Coronal mass ejection: A CME typically arrives 18 hours to several days later, driving geomagnetic storms that can induce currents in power grids and make compass readings unstable.

- Upper-atmosphere response: Heating and expansion increase drag on low-orbiting satellites, while enhanced particle precipitation produces auroras. Increased drag can also hasten the decay of space debris.

ESA advises that forecasts for this event carry inherent uncertainties and will be updated as new measurements are assimilated. For the latest details, consult the ESA space weather page.