The European Space Agency has compiled the first global catalogue of Martian dust devils with motion measurements, tracking 1,039 tornado-like vortices across two decades of imagery from Mars Express and the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter. The analysis, published in Science Advances, indicates near-surface winds can reach up to 44 m/s (158 km/h), substantially faster than many models predicted, and provides a new foundation for understanding dust lifting, transport, and seasonal weather on Mars. The catalogue and methods are expected to inform landing risk assessments, rover power management, and future observation strategies. Source: European Space Agency report.

What the catalogue reveals

- Scope and coverage: 1,039 dust devils identified globally; motion vectors derived for 373 events spanning diverse terrains, including volcanic provinces and plains.

- Wind speeds: Peak horizontal speeds up to 44 m/s, exceeding values measured in situ by rovers and outpacing predictions from prevailing Mars weather models in many regions.

- Geographic clustering: High activity in source regions such as Amazonis Planitia, where fine dust and sand are abundant, while dust devils still occur planet-wide.

- Seasonality and timing: Most events arise in spring and summer, lasting minutes and peaking between local solar times of late morning to early afternoon.

- Dust lifting implications: Faster-than-expected winds suggest greater dust entrainment in some areas, with consequences for temperature regulation, cloud nucleation, and atmospheric water loss.

Why dust devils matter for Mars climate and operations

Dust is a dominant driver of Martian weather. It can cool daytime and warm nighttime temperatures, seed clouds, and influence when and where water vapor escapes to space. Integrating thousands of motion-derived wind measurements improves global circulation models, supporting more accurate forecasts of near-surface wind patterns and dust activity.

Operationally, these insights help mission planners estimate dust deposition on solar arrays, schedule self-cleaning strategies, and assess wind conditions for entry, descent, and landing. ESA’s Rosalind Franklin rover, planned for 2030, already factors dust storm climatology into its timeline; site-specific wind mapping can further reduce risk and improve power and imaging performance after touchdown.

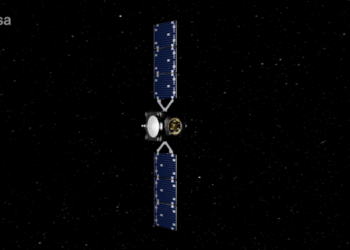

How the team measured wind from orbit

Neither Mars Express nor ExoMars TGO was designed to measure winds, but both produce images by combining multiple channels captured seconds apart. Moving features create subtle offsets between channels. Researchers trained a neural network to detect dust devils, then measured their displacements across the time-staggered channels to calculate speeds and directions.

Mars Express imaging sequences span delays of roughly 7–19 seconds across up to five channels, enabling estimates of speed as well as lateral wobble and short-term acceleration. ExoMars CaSSIS provides paired views separated by about 1 second (color) or 46 seconds (stereo), allowing longer-baseline displacement measurements. This repurposing of minor image offsets turns a typical processing artifact into a quantitative wind probe.

What comes next

The dust devil catalogue is public and continues to grow as both spacecraft acquire new images. The team is directing more observations to high-yield regions and time windows and coordinating cross-mission imaging of the same events to validate motion retrievals. As statistics expand, modelers can refine localized wind climatologies, improve dust lifting parameterizations, and better anticipate environmental conditions at future landing sites.

For programmatic stakeholders, the results provide actionable data for trajectory design margins, operations planning, and long-lived surface power strategies. For the science community, the dataset delivers a new global map of near-surface winds derived directly from motion, bridging gaps between point measurements on the ground and broad-scale atmospheric models. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adw5170.