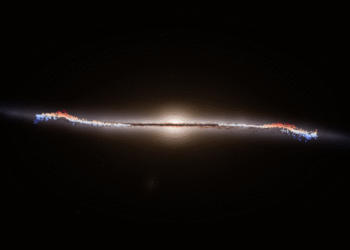

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has imaged an exceptionally long protostellar jet stretching roughly 8 light-years across the Sharpless 2-284 (Sh2-284) star-forming region on the outer edge of the Milky Way. The observation provides new evidence that jet size scales with the mass of the forming star and strengthens the case for core accretion as a dominant pathway for building massive stars. The discovery, about 15,000 light-years away, is detailed in a study accepted by The Astrophysical Journal and highlighted in a NASA release.

What Webb Saw

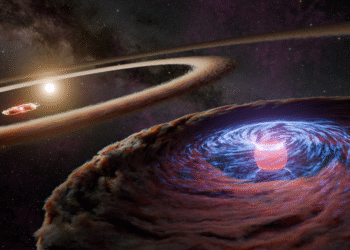

Webb’s NIRCam infrared imaging reveals a highly collimated, twin-lobed outflow with intricate filaments, knots, and bow shocks, signatures of a jet plowing into surrounding gas and dust. The central protostar is estimated to be about 10 times the mass of the Sun and is still accreting material. The jet’s morphology encodes a long formation history, with the oldest structures extended farthest along the outflow axis and younger features trailing behind.

- Jet length: ~8 light-years

- Location: Sh2-284, ~15,000 light-years away

- Driving source: ~10-solar-mass protostar (still growing)

- Imaging instrument: JWST NIRCam

- Environment: Low metallicity cluster on the Milky Way’s periphery

Why It Matters

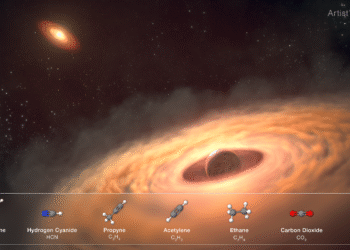

Protostellar jets are powered by gravitational energy released as material accretes through a disk onto a young star. The scale and symmetry of the Sh2-284 outflow imply a relatively stable disk and magnetic launching geometry consistent with core accretion models of massive star formation. This stands in contrast to “competitive accretion” scenarios that predict more chaotic disk reorientation and corresponding jet twists. The clear, nearly antiparallel lobes in Webb’s image support mass growth through a persistent disk, with the jet acting as a regulated exhaust.

The result also indicates that jet properties scale with protostellar mass: more massive progenitors appear to drive larger, more energetic outflows. Establishing this relationship across mass regimes provides a unifying framework for jet physics from Sun-like stars to high-mass protostars.

A Frontier Laboratory for Low-Metallicity Star Formation

Sh2-284 lies nearly twice as far from the Galactic center as the Sun, in a region with fewer heavy elements. This low-metallicity environment serves as a local analog for earlier cosmic epochs, offering a window into how massive stars may have formed when the universe contained fewer metals. Within the host protocluster, hundreds of stars are still coalescing, making it a rich field for testing how metallicity influences disk stability, accretion rates, and jet feedback.

Multi-Observatory Context and Next Steps

Complementary data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) identify an additional dense core in the region that may represent an earlier formation phase, suggesting that massive star growth is ongoing across the cluster. Future Webb spectroscopy and time-domain imaging could map jet velocities, excitation conditions, and magnetic field coupling, while longer-wavelength interferometry can probe disk structure, mass infall, and fragmentation.

Together, these observations build an increasingly coherent picture: in low-metallicity environments at the Milky Way’s outskirts, massive stars can assemble via stable, long-lived disks that launch powerful, well-aligned jets. Webb’s sensitivity and resolution in the infrared continue to reveal the mechanics of star birth across mass scales and galactic environments.

Source: NASA Science: “NASA’s Webb Observes Immense Stellar Jet on Outskirts of Our Milky Way”