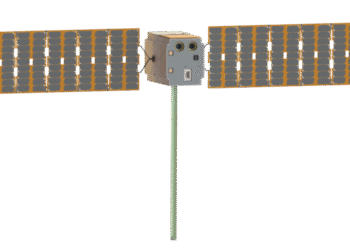

Researchers supported by NASA have demonstrated a straightforward seismic survey technique to locate subsurface voids such as lava tubes and caves—sites that could offer natural shielding for future crews on the Moon and Mars. Field trials conducted near Flagstaff, Arizona, and Tulelake, California, used a 10‑pound (4.5‑kilogram) sledgehammer striking a steel plate to send vibrations into the ground. Signals scattered back to a line of detectors revealed buried cavities comparable to those expected on other worlds. The proof‑of‑concept results, reported in Geophysical Research Letters, are part of NASA’s GEODES project within the Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute, supporting upcoming Artemis lunar missions.

How the test worked

The team executed a series of controlled hammer strikes—one impact every 1 meter—along a 125‑meter survey line above known lava tubes and caves. The approach is analogous to a medical CT scan: each impact injects seismic energy that reflects and scatters off subsurface structures, which are then recorded by a string of ground sensors. The data indicated that the method can detect voids beneath the surface using compact, low‑power equipment suitable for planetary analog sites.

Why underground shelters matter

Lunar and Martian lava tubes formed during earlier periods of volcanic activity. Their rock overburden could provide passive protection from radiation, micrometeoroids, and extreme temperature swings—key hazards for sustained human and robotic operations. Identifying such features efficiently is a priority for surface mission planning and site certification.

- Risk reduction: Scouts stable voids before astronaut traverses and rover deployments.

- Logistics: Lightweight hardware complements radar and lidar for rapid ground truth.

- Habitation potential: Candidate locations for laboratories, storage, and sheltered habitats.

Scaling for the Moon and Mars

While the field tests used a hand‑held sledgehammer to validate the concept, replacing it with a mechanized drop‑weight or high‑speed impactor could increase penetration depth and data quality in low‑gravity, airless environments. The technique can be paired with orbital imagery and other in‑situ sensors to refine subsurface models and prioritize targets during Artemis surface campaigns and future Mars missions.

What comes next

Future work aims to extend depth sensitivity, adapt acquisition to robotic platforms, and refine inversion algorithms tuned to lunar regolith and basaltic terrains. Combined with remote sensing, these surveys could map void geometry, identify entrances, and help assess structural stability—key inputs for mission architecture and long‑duration operations.

Source: NASA Science